Validating a Lean Proof

This section discusses how to validate a proof expressed in Lean.

Depending on the circumstances, additional steps may be recommended to rule out misleading proofs. In particular, it matters a lot whether one is dealing with an honest proof attempt, and needs protection against only benign mistakes, or a possibly-malicious proof attempt that actively tries to mislead.

In particular, we use honest when the goal is to create a valid proof.

This allows for mistakes and bugs in proofs and meta-code (tactics, attributes, commands, etc.), but not for code that clearly only serves to circumvent the system (such as using the debug.skipKernelTC).

Note that the unsafe marker on API functions is unrelated to whether this API can be used in an dishonest way.

In contrast, we use malicious to describe code to go out of its way to trick or mislead the user, exploit bugs or compromise the system. This includes un-reviewed AI-generated proofs and programs.

Furthermore it is important to distinguish the question “does the theorem have a valid proof” from “what does the theorem statement mean”.

Below, an escalating sequence of checks are presented, with instructions on how to perform them, an explanation of what they entail and the mistakes or attacks they guard against.

The Blue Double Check Marks

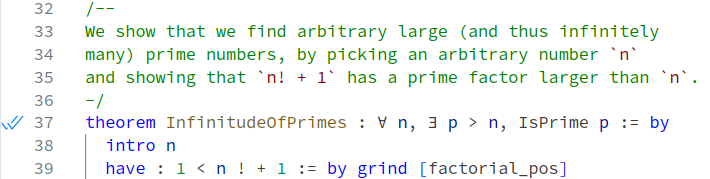

In regular everyday use of Lean, it suffices to check the blue double check marks next to the theorem statement for assurance that the theorem is proved.

Instructions

While working interactively with Lean, once the theorem is proved, blue double check marks appear in the gutter to the left of the code.

Significance

The blue ticks indicate that the theorem statement has been successfully elaborated, according to the syntax and type class instances defined in the current file and its imports, and that the Lean kernel has accepted a proof of that theorem statement that follows from the definitions, theorems and axioms declared in the current file and its imports.

Trust

This check is meaningful if one believes the formal theorem statement corresponds to its intended informal meanings and trusts the authors of the imported libraries to be honest, that they performed this check, and that no unsound axioms have been declared and used.

Protection

This check protects against

-

Incomplete proof (missing goals, tactic error) of the current theorem

-

Explicit use of

sorryin the current theorem -

Honest bugs in meta-programs and tactics

-

Proofs still being checked in the background

Comments

In the Visual Studio Code extension settings, the symbol can be changed. Editors other than VS Code may have a different indication.

Running lake build +Module, where Module refers to the file containing the theorem, and observing success without error messages or warnings provides the same guarantees.

Printing Axioms

The blue double check marks appear even when there are explicit uses of sorry or incomplete proofs in the dependencies of the theorem.

Because both sorry and incomplete proofs are elaborated to axioms, their presence can be detected by listing the axioms that a proof relies on.

Instructions

Write #print axioms thmName after the theorem declaration, with thmName replaced by the name of the theorem and check that it reports only the built-in axioms propext, Classical.choice, and Quot.sound.

Significance

This command prints the set of axioms used by the theorem and the theorems it depends on. The three axioms above are standard axioms of Lean's logic, and benign.

-

If

sorryAxis reported, then this theorem or one of its dependencies usessorryor is otherwise incomplete. -

If

Lean.trustCompileris reported, then native evaluation is used; see below for a discussion. -

Any other axiom means that a custom axiom was declared and used, and the theorem is only valid relative to the soundness of these axioms.

Trust

This check is meaningful if one believes the formal theorem statement corresponds to its intended informal meanings and one trusts the authors of the imported libraries to be honest.

Protection

(In addition to the list above)

-

Incomplete proofs

-

Explicit use of

sorry -

Custom axioms

Comments

At the time of writing, the Lean.Parser.Command.printAxioms : command#print axioms command does not work in a module.

To work around this, create a non-module file, import your module, and use Lean.Parser.Command.printAxioms : command#print axioms there.

Re-Checking Proofs with lean4checker

There is a small class of bugs and some dishonest ways of presenting proofs that can be caught by re-checking the proofs that are stored in .olean files when building the project.

Instructions

Build your project using lake build, run lean4checker --fresh on the module that contains the theorem of interest, and check that no error is reported.

Significance

The lean4checker tool reads the declarations and proofs as they are stored by lean during building (the .olean files), and replays them through the kernel.

It trusts that the .olean files are structurally correct.

Trust

This check is meaningful if one believes the formal theorem statement corresponds to its intended informal meanings and believes the authors of the imported libraries to not be very cunningly malicious, and to neither compromise the user’s system nor use Lean’s extensibility to change the interpretation of the theorem statement.

Protection

(In addition to the list above)

-

Bugs in Lean’s core handling of the kernel’s state (e.g. due to parallel proof processing, or import handling)

-

Meta-programs or tactics intentionally bypassing that state (e.g. using low-level functionality to add unchecked theorems)

Comments

Since lean4checker reads the .olean files without validating their format, this check is prone to an attacker crafting invalid .olean files (e.g. invalid pointers, invalid data in strings).

Lean tactics and other meta-code can perform arbitrary actions when run. Importing libraries created by a determined malicious attacker and building them without further protection can compromise the user's system, after which no further meaningful checks are possible.

We recommend running lean4checker as part of CI for the additional protection against bugs in Lean's handling of declaration and as a deterrent against simple attacks.

The lean-action GitHub Action provides this functionality by setting lean4checker: true.

Without the --fresh flag the tool can be instructed to only check some modules, and assume others to be correct (e.g. trusted libraries), for faster processing.

Gold Standard: comparator

To protect against a seriously malicious proof compromising how Lean interprets a theorem statement or the user's system, additional steps are necessary. This should only be necessary for high risk scenarios (proof marketplaces, high-reward proof competitions).

Instructions

In a trusted environment, write the theorem statement (the ”challenge”), and then feed the challenge as well as the proposed proof to the comparator tool, as documented there.

Significance

Comparator will build the proof in a sandboxed environment, to protect against malicious code in the build step. The proof term is exported to a serialized format. Outside the sandbox and out of the reach of possibly malicious code, it validates the exported format, loads the proofs, replays them using Lean's kernel, and checks that the proved theorem statement matches the one in the challenge file.

Trust

This check is meaningful if the theorem statement in the trusted challenge file is correct and the sandbox used to build the possibly-malicious code is safe.

Protection

(In addition to the list above)

-

Actively malicious proofs

Comments

At the time of writing, comparator uses only the official Lean kernel.

In the future it will be easy to use multiple, independent kernel implementations; then this will also protect against implementation bugs in the official Lean kernel.

Remaining Issues

When following the gold standard of checking proofs using comparator, some assumptions remain:

-

The soundness of Lean’s logic.

-

The implementation of that logic in Lean’s kernel (for now; see comment above).

-

The plumbing provided by the

comparatortool. -

The safety of the sandbox used by

comparator -

No human error or misleading presentation of the theorem statement in the trusted challenge file.

On Lean.trustCompiler

Lean supports proofs by native evaluation.

This is used by the decideLean.Parser.Tactic.decide : tactic`decide` attempts to prove the main goal (with target type `p`) by synthesizing an instance of `Decidable p`

and then reducing that instance to evaluate the truth value of `p`.

If it reduces to `isTrue h`, then `h` is a proof of `p` that closes the goal.

The target is not allowed to contain local variables or metavariables.

If there are local variables, you can first try using the `revert` tactic with these local variables to move them into the target,

or you can use the `+revert` option, described below.

Options:

- `decide +revert` begins by reverting local variables that the target depends on,

after cleaning up the local context of irrelevant variables.

A variable is *relevant* if it appears in the target, if it appears in a relevant variable,

or if it is a proposition that refers to a relevant variable.

- `decide +kernel` uses kernel for reduction instead of the elaborator.

It has two key properties: (1) since it uses the kernel, it ignores transparency and can unfold everything,

and (2) it reduces the `Decidable` instance only once instead of twice.

- `decide +native` uses the native code compiler (`#eval`) to evaluate the `Decidable` instance,

admitting the result via an axiom. This can be significantly more efficient than using reduction, but it is at the cost of increasing the size

This can be significantly more efficient than using reduction, but it is at the cost of increasing the size

of the trusted code base.

Namely, it depends on the correctness of the Lean compiler and all definitions with an `@[implemented_by]` attribute.

Like with `+kernel`, the `Decidable` instance is evaluated only once.

Limitation: In the default mode or `+kernel` mode, since `decide` uses reduction to evaluate the term,

`Decidable` instances defined by well-founded recursion might not work because evaluating them requires reducing proofs.

Reduction can also get stuck on `Decidable` instances with `Eq.rec` terms.

These can appear in instances defined using tactics (such as `rw` and `simp`).

To avoid this, create such instances using definitions such as `decidable_of_iff` instead.

## Examples

Proving inequalities:

```lean

example : 2 + 2 ≠ 5 := by decide

```

Trying to prove a false proposition:

```lean

example : 1 ≠ 1 := by decide

/-

tactic 'decide' proved that the proposition

1 ≠ 1

is false

-/

```

Trying to prove a proposition whose `Decidable` instance fails to reduce

```lean

opaque unknownProp : Prop

open scoped Classical in

example : unknownProp := by decide

/-

tactic 'decide' failed for proposition

unknownProp

since its 'Decidable' instance reduced to

Classical.choice ⋯

rather than to the 'isTrue' constructor.

-/

```

## Properties and relations

For equality goals for types with decidable equality, usually `rfl` can be used in place of `decide`.

```lean

example : 1 + 1 = 2 := by decide

example : 1 + 1 = 2 := by rfl

```

+native tactic or internally by specific tactics (bv_decide in particular) and produces proof terms that call compiled Lean code to do a calculation that is then trusted by the kernel.

Specific uses wrapped in honest tactics (e.g. bv_decide) are generally trustworthy.

The trusted code base is larger (it includes Lean's compilation toolchain and library annotations in the standard library), but still fixed and vetted.

General use (decideLean.Parser.Tactic.decide : tactic`decide` attempts to prove the main goal (with target type `p`) by synthesizing an instance of `Decidable p`

and then reducing that instance to evaluate the truth value of `p`.

If it reduces to `isTrue h`, then `h` is a proof of `p` that closes the goal.

The target is not allowed to contain local variables or metavariables.

If there are local variables, you can first try using the `revert` tactic with these local variables to move them into the target,

or you can use the `+revert` option, described below.

Options:

- `decide +revert` begins by reverting local variables that the target depends on,

after cleaning up the local context of irrelevant variables.

A variable is *relevant* if it appears in the target, if it appears in a relevant variable,

or if it is a proposition that refers to a relevant variable.

- `decide +kernel` uses kernel for reduction instead of the elaborator.

It has two key properties: (1) since it uses the kernel, it ignores transparency and can unfold everything,

and (2) it reduces the `Decidable` instance only once instead of twice.

- `decide +native` uses the native code compiler (`#eval`) to evaluate the `Decidable` instance,

admitting the result via an axiom. This can be significantly more efficient than using reduction, but it is at the cost of increasing the size

This can be significantly more efficient than using reduction, but it is at the cost of increasing the size

of the trusted code base.

Namely, it depends on the correctness of the Lean compiler and all definitions with an `@[implemented_by]` attribute.

Like with `+kernel`, the `Decidable` instance is evaluated only once.

Limitation: In the default mode or `+kernel` mode, since `decide` uses reduction to evaluate the term,

`Decidable` instances defined by well-founded recursion might not work because evaluating them requires reducing proofs.

Reduction can also get stuck on `Decidable` instances with `Eq.rec` terms.

These can appear in instances defined using tactics (such as `rw` and `simp`).

To avoid this, create such instances using definitions such as `decidable_of_iff` instead.

## Examples

Proving inequalities:

```lean

example : 2 + 2 ≠ 5 := by decide

```

Trying to prove a false proposition:

```lean

example : 1 ≠ 1 := by decide

/-

tactic 'decide' proved that the proposition

1 ≠ 1

is false

-/

```

Trying to prove a proposition whose `Decidable` instance fails to reduce

```lean

opaque unknownProp : Prop

open scoped Classical in

example : unknownProp := by decide

/-

tactic 'decide' failed for proposition

unknownProp

since its 'Decidable' instance reduced to

Classical.choice ⋯

rather than to the 'isTrue' constructor.

-/

```

## Properties and relations

For equality goals for types with decidable equality, usually `rfl` can be used in place of `decide`.

```lean

example : 1 + 1 = 2 := by decide

example : 1 + 1 = 2 := by rfl

```

+native or direct use of Lean.ofReduceBool) can be used to create invalid proofs whenever the native evaluation of a term disagrees with the kernel's evaluation.

In particular, for every implemented_by/extern attribute in libraries it becomes part of the trusted code base that the replacement is semantically equivalent.

All these uses show up as an axiom Lean.trustCompiler in Lean.Parser.Command.printAxioms : command#print axioms.

External checkers (lean4checker, comparator) cannot check such proofs, as they do not have access to the Lean compiler.

When that level of checking is needed, proofs have to avoid using native evaluation.